Using Psychometrics for Strategic Decision-Making

with Araz Najarian

The Business Simplicity Podcast hosted by Chris Parker

Episode #227 published on 20 November 2025

This episode explores why some organizations thrive for over a century while others fade away, and how psychometrics can unlock the answers. Chris Parker is joined by Araz Narjarian, a partner at ELP and expert in organizational psychology, who examines the hidden drivers of sustained relevance and growth. The conversation goes deep into how leaders can connect external market realities with internal capabilities to create lasting value.

Araz Narjarian joined ELP during the 2008 financial crisis, at a pivotal moment when many were seeking security rather than opportunity. Instead of choosing the predictable path into private equity, he took a chance on ELP’s partnership model, asking the bold question: “Why don’t you actually try that out?” That decision led to years of partnership and a role in driving the firm’s continued growth and relevance. His expertise lies in helping organizations navigate the gap between strategic intent and operational reality.

Listeners will walk away with a framework for understanding why organizational longevity has little to do with industry or macroeconomic factors, and everything to do with how companies perceive value through the customer’s eyes. Araz challenges the notion that strategy is an intellectual exercise disconnected from execution, offering instead a practical lens on how to organize resources, compensate people, and fuel sustainable growth. The episode dismantles the myth that brainy strategic frameworks alone drive success.

For executives navigating complexity, this conversation is a reminder that staying relevant requires constant connection to the outside world and the discipline to create value as customers define it. These insights matter now more than ever as leaders face markets defined by rapid change and must organize themselves not just to survive, but to pay people well, reinvest intelligently, and drive compounding growth across generations.

Araz Narjarian is a partner at ELP with deep expertise in psychometrics and organizational development. He joined the firm during the 2008 financial crisis and chose the entrepreneurial path of partnership over more traditional private sector opportunities. Over his tenure, he has been instrumental in helping ELP remain relevant and grow across changing business cycles. His work focuses on the intersection of human behavior, organizational systems, and strategic execution, particularly exploring why some companies sustain success across decades while others struggle despite seemingly sound strategies. He was invited onto the show for his insights into what truly drives organizational longevity and how leaders can bridge the gap between strategy and practical execution.

Contact Details

- Company: https://www.elpnetwork.com/en

- LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/araznajarian/

Key Discussion Points

- Why do some organizations stay relevant for 100+ years while others fade? Research shows it has nothing to do with industry differences or macroeconomic factors – it comes down to how connected they stay to the outside world and how they create value as perceived by the customer.

- What’s the real purpose of organizing a business? To successfully organize ourselves to make money so we can pay people, reinvest in the business, and fuel sustainable growth.

- Why do many strategic practices fail in the real world? Because they’re run as “egghead” or overly intellectual exercises disconnected from execution, where strategy becomes “some static stuff we have to do” rather than a living framework for action.

- How can psychometrics help with business strategy? By providing deeper insight into how people and organizations actually behave versus how we think they should behave, closing the gap between intent and reality.

- What separates companies that execute well from those that just strategize? The ability to translate customer-perceived value into practical systems that people can actually execute day-to-day.

- What role does partnership culture play in sustained success? It creates alignment between personal incentives and long-term organizational health, as demonstrated by Araz’s decision to join ELP as a partner during uncertain times.

- Why is external connection more important than internal optimization? Because value is defined by the market and customers, not by internal metrics – companies that lose touch with the outside world eventually lose relevance regardless of operational efficiency.

Transcript

Chris Parker: Welcome back to the Business Simplicity podcast. This is Chris Parker, and I’m having a conversation with Araz Najarian. She’s a partner with the ELP network. I’m associated with ELP as well and I’ve done some projects with them over the years. Their tagline is “realizing breakthroughs,” and I know them for working with management teams and executive teams, particularly in scale-up, change, and large strategic shift moments. In a moment, I’ll let Araz share deeper into what ELP is doing.

Recently, part of the network had a conversation about psychometrics, and that was hosted by Araz and Michael Newman, another associated member with ELP. I thought it was really fascinating, and some of the insights that came back… I just couldn’t resist. I said, “Hey Araz, can we please talk about this and unpack this? I want to go deeper.” I love having these conversations because this is what I learn and connect.

So we’re going to dive into psychometrics in the context of business leadership, strategizing, and decision-making, and hopefully, when not to use them or how not to use them as well. And soon we’ll define what psychometrics actually are. But Araz, thank you so much for joining. Maybe if you want to express a bit deeper about ELP and the type of work you do there, and then we’ll turn the corner and figure out what psychometrics is all about.

Araz Najarian: Super. Well, I joined ELP quite some time ago, actually. It was in the midst of the first financial crisis of the 2000s, back in 2008. I was also at a period where I was searching for my next step. A mentor of mine from the ISC network, Fernando Lanzer, said, “Maybe before jumping into a single company in the private sector, why don’t I introduce you to the partners of the ELP network?” He introduced me to Nick Van Heck and Tom Cummings, who were both partners at the time, and said, “Why don’t you actually try that out?”

What really attracted me, and why I ended up staying so many years later and becoming part of the partnership, was that when they created the company, there were two main drivers.

One was asking the question: Why is it that some organizations manage to stay relevant and continue growing for 100-plus years, and others fade away? What really makes the difference? The research showed that it’s nothing to do with industry differences or macroeconomic factors. It all comes down to: How are you able to stay connected to the outside world? How do you continue to create value for others—value as perceived by the customer, and value beyond just price?

And then, are we able to successfully organize ourselves to make money so we can pay people, pay our suppliers, and keep reinvesting in the business? Continuing that pattern of renewal is what’s going to help fuel that growth.

To enable that, they saw that some practices in organizations were being run in a very disconnected way. For example, for the strategy process, all the senior people go away and do this “egghead” type of brainy exercise. Then they come back and tell everybody, “Here’s what we’re going to do, here’s why, and here’s what you’re supposed to do.” That’s very much strategy as execution, which, more and more, we see really does not work. Strategy is not some static document. It’s actually strategizing—it’s strategy as learning.

On the other hand, you look at executive leadership development. People would go away on these wonderful offsites, have profound insights, and yet when they’d come back, engagement scores or other sentiment metrics were abysmal. How do people feel about their manager? Do I belong here? Do I feel invited? If you’re creating that kind of workplace, that’s a workforce you have to drag along to get results, versus everybody showing up every day excited and ready to contribute.

That’s essentially where we try to play: to support that renewal of growth and bring strategizing and leadership together.

Chris Parker: Did you guys find a causality from that second order of engagement with that 100-year-ambition of a healthy company? I hope that’s true. The intention is: what makes these long-term sustainable companies is the connection with the outside (a leadership action) and then strategizing and engaging. Are those two concepts the main things that contribute to long-term sustainability, do you think?

Araz Najarian: Well, we looked at it and said those dynamics are actually quite leading and have a heavy weight in the ability to find new ways of creating value, because the world around you also changes. You see that with companies that have been successful, but when competition or new technology comes along and they’re unable to adapt, they’re in a difficult situation playing catchup.

I think what we’re always doing, in terms of our connection to academia, is continuing to renew that research, but also research into the practices. How can some of those practices—that are less tangible to measure than financial metrics—give a sign of whether we are actually healthy and on the path that’s going to eventually show up in our financials?

Chris Parker: Yeah, I think so. You mentioned academic—it’s my association with ELP where I met Amy Edmondson from Harvard around psychological safety and “positive failing.” And I remember when I first met Nick Vanhack, the partner you mentioned, probably 20 years ago when I was with LeasePlan in an executive program. He was simplifying some of these concepts, like value creation versus value capture. People talk about that a lot nowadays, but separating those intents was profound for me at that time. Would you mind diving into that? What is value creation versus value capture? And then I’m curious, how does psychometrics fit into all this?

Araz Najarian: That’s a very good question. We could do hours on this! When you dive into value creation, it’s based on the eyes of the customer. So it’s not something you can consistently and easily measure, because it’s very much a perception. Where I’ve seen the value of decoupling those two… if you look at Michael Porter, he started to talk a lot about “shared value.” That was eye-opening for many because you decouple value purely from shareholder value.

What I like about value creation vs. value capturing is how it separates and shows that stakeholders can have competing interests. There are businesses that make a lot of money, are highly profitable, and make their shareholders very happy, but have a customer base that isn’t satisfied. They may feel stuck, like in a monopoly.

What happens is, eventually, when competition does come along, you start losing your topline because the captive customers you had leave. Then you might start restructuring or buying revenue through acquisitions, but you’re not fundamentally looking at: Who is my customer? What am I serving? And how am I looking at value for them?

Chris Parker: Can you give an example of an engagement when you’re talking about that sustainable business ambition—helping an organization’s leadership connect to the outside world while strategizing to engage the rest of the company, all while keeping an eye on value capture versus value creation? Is this the essence of the engagements ELP steps into?

Araz Najarian: Yeah, it’s definitely one of the iconic pieces. You talked about our tagline, “realizing breakthroughs.” For us, it’s realizing breakthroughs in the context of growth. We talk about “creating space for growth.” We’re looking at growth not purely as you may end up bigger; that’s not necessarily the purpose. It’s not just more of the same.

As Roger Martin talks about: are we exploiting or are we exploring? There’s the part of growth that’s exploration, and that’s very much transformative. So the type of engagement we have really depends on what’s happening in the organization and where the entry point is. In a lot of cases, it does start with the leadership team, because they are the ones setting the context.

I think this ties into psychometrics. When we prepare for an engagement, like an offsite with a leadership team, we talk to the people beforehand to get to know who is in the team and how they are looking at the current situation. Oftentimes, what I hear back is a feeling of doubt: “I think we’re more or less aligned, but I’m not really sure,” or, “We have a plan, but I don’t know how they’re feeling about it.”

It’s the things that are left unsaid, what’s sitting under the surface that doesn’t come up in the day-to-day business. It doesn’t come up in a management meeting because time is too short, or because of that interpersonal risk Amy Edmondson points out. Can I actually bring something up that’s challenging, or a criticism, without people perceiving me as being negative?

Teams have offsites all the time, but sometimes they just become an extended management meeting, which is a pity. Those are the only moments we have as a leadership team to create space to surface those things we aren’t even conscious of and get really aligned on where we actually are today. We all have different definitions of the challenges or the assets we should be leveraging.

Some of that comes down to fundamentally different preferences and behaviors in how we want to problem-solve. That’s where I find tools like psychometrics, depending on how we use them, can be so powerful in a team setting. We get a language to understand why you are thinking that way.

Chris Parker: I was first introduced to psychometrics in my MBA, and later when I was running an international project for LeasePlan, we ran the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) for the whole team. It was really revealing. It peeled back another layer of understanding myself, and through that, understanding how others might experience me. And I can see them through a different lens.

When you understand how personalities shift by context—at work, at home, or under stress when a shadow dimension comes out—I think it creates a space of acceptance and sometimes forgiveness. “Oh, that’s who this person is.” Even though they’re behaving oddly, I can see beyond the behavior.

I’ve always been interested in these things to understand myself better. But maybe you can give it a stab: What is psychometrics, and what are some examples? I mentioned Myers-Briggs, but there’s a whole menagerie of different approaches.

Araz Najarian: Chris, before I do that, can I ask you a question back? What you just described, it sounds like the first time you were introduced to something like an MBTI was in a team context?

Chris Parker: Yes.

Araz Najarian: And was that also… you were guided through it?

Chris Parker: Absolutely. The first time was at Nyenrode for the MBA. The process was described to us, we were given the assessment, and we were also given a number of warnings. I found that really interesting. It was an MBA setting, so we were able to share, and it was a bonding thing. We were like, “Oh, I understand you better now.”

So then, when I was tasked to create a company in Ireland, we had about 50 people coming together—internals and externals, people who had never worked together. I was seeking connection and understanding quickly. We did some offsites, and that was the first time I used this type of thing for a team I was responsible for. It was a conversation starter. I think that was the biggest thing.

Araz Najarian: Yeah. I was curious because the first time I was ever introduced to MBTI, it was not a good experience. For me, part of it was because the debriefing was not done very well. We didn’t get out of it what you just described—building understanding and curiosity. It ran the risk of stereotyping and labeling.

It was later on, in a different context, that I was reintroduced to it (I can’t remember if it was MBTI or Insights, another Jungian-based tool), and the debrief made such a difference. We had someone who could give warnings, asking, “Why are we using this? What is it going to say about you?” Keep in mind, no human can be boxed and completely categorized. It sounds like your first introduction, having a good guide, brought benefit rather than just becoming a label.

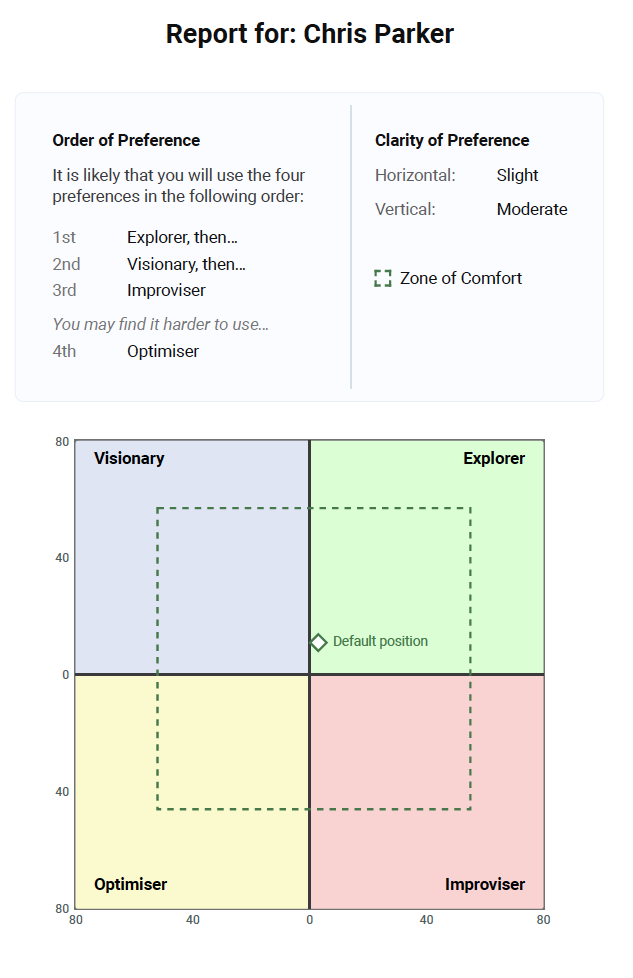

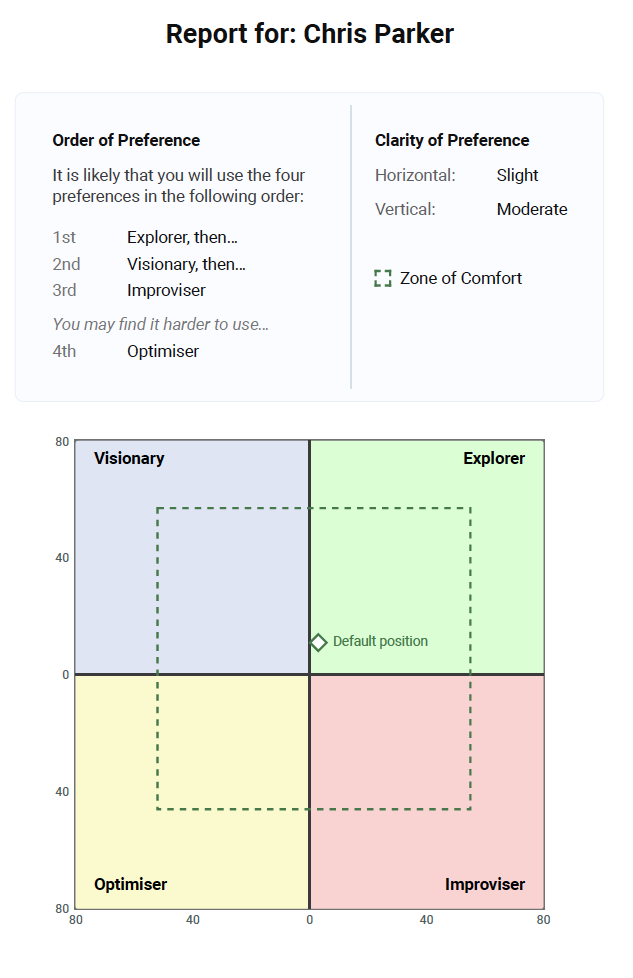

Chris Parker: I certainly didn’t feel boxed. For me, it’s been very consistent over the years: I’m an INTP (Introvert, Intuitive, Thinking, Perceiver) as a natural state. I started to identify with that archetype—kind of a visionary, architect, problem-solver. It gave me validation, like, “Oh, I feel comfortable in my skin when I hear those words.”

What I also realized is that in work, I had trained myself to be in the “J” (Judging). And I noticed this because we’re going to talk about this SPI report… I think there was some J coming out of that as well.

For people who don’t know MBTI, that last acronym (Perceiving vs. Judging) is basically: do you like to keep things open, or do you like to close things and be definitive? In my normal life, I like keeping my options open. But at work, I’ve had to learn that, no, you’ve got to make a decision. Maybe that was a survival response in the corporate world, where having options open forever isn’t always appreciated.

Araz Najarian: It’s a very human thing. A part of us wants to explore, and another part wants to organize the world and bring clarity and stability. We may have a preference, but there’s a difference between having a preference and having a skill. Sometimes people can have a preference and be completely incompetent in that preference. If you like exploring options, you may be very poor at the quality of options you explore.

That’s an important distinction. All psychometric tools, even MBTI, come under criticism. Big Five, which is more robust, also comes under criticism because it’s still self-reporting. And it doesn’t take into account that our brains are neuroplastic; we’ve proven we can teach old dogs new tricks. We can always grow and stretch.

Chris Parker: You mentioned this meeting we had, and I think it’s a little unfair to the listeners because we were there. Why was this meeting held? I checked in, and there were probably 15 people on the call, all deeply skilled in this. It was a very rich conversation. Why was that meeting held, and for you, what were the main outcomes?

Araz Najarian: For me, why it was important—and something I want to keep doing—is, one, psychometrics have come under criticism, just like any tool, (e.g., Balanced Scorecard).

Second, it’s a developing field. There are many more insights now from things like neuro-leadership. For example, Steven Okonoa (who couldn’t join that call) is involved with something called “NeuroColor,” developed by Dr. Helen Fischer. They developed it based on putting people through MRI scans to see which parts of the brain light up. So, it’s important to stay up-to-date on our evolving understanding of the human brain and how it influences our decisions and behaviors. Those were the two main reasons for the conversation.

Chris Parker: I think with the advances in technology and psychology, this is evolving. MBTI is probably 40 years old. Then you have the colors, DISC, etc.

What were the outcomes? I think one reason these things get criticized is they’re used inappropriately. In my world, Agile, Scrum, and SAFe are criticized, but it’s rare that someone actually took the time to understand what it was about. Instead, somebody comes in and does a mechanical implementation—”We have to show up to these meetings and do these tasks”—without any understanding of the intention behind the practices. A lot of great ideas are ruined because they’re used inappropriately.

So let’s go back to the principles. What were the highlight principles that came out of this expert group talking about psychometrics?

Araz Najarian: One of them is spot on what you just mentioned: Why are you actually using a psychometric? For what purpose? What do you want to get out of it? When that’s not clear, it can be used inappropriately.

The main principle coming out of the group is that these are tools better used for development than they are for selection. There’s a tendency for people to get eager, see their team picture, and say, “Oh, we’re missing this profile.” No, that’s not the point. You’re not going to use this to populate your team, because they’re not predictive and they only tell you a fraction of what a person is.

The other thing was the importance of the debrief. It’s not something you just take away for yourself. You need an experienced professional to help debrief the report. A professional can take things out of a report that are not written in the report; they understand you, your team, and your context. The richness is in the conversation; the report is just an input.

What I loved that came out of this conversation was that we landed on: Use psychometrics to ask better questions, not to give answers.

It’s not, “Now I have an answer so I can completely understand myself.” It’s, “Now I have a map that allows me to continue to explore the territory.”

Chris Parker: Can you give an example of that? “Ask better questions instead of providing answers.” What do you mean?

Araz Najarian: It comes down to asking questions to understand each other better; to get to the, “But why is it that you’re doing it that way?”

Chris Parker: I think for me, it’s also looking at understanding myself first. It allows me to ask more questions about myself. For example, with introversion/extroversion, I love performing on stages and doing workshops, but I know I will be drained afterwards. I now have the language to tell people, “Yes, I’m going to be performing, I’ll be rocking it, and I will need to invert afterwards. Just give me some time to go read my book.”

I’ve never done this with my two boys, but I can see one is an extreme introvert and the other an extrovert. You can just watch these conflicts happen! It helps me understand, and then I can bring that language in and give forgiveness. It’s like, “Okay, we’re all tired. When you’re tired, you want to talk more; when you’re tired, you want to go in a hole. Those things are not compatible. Let’s find ways to give each other what we need.”

Araz Najarian: Absolutely. What’s interesting is if you look at classical brainstorming or strategizing processes, some can be heavily biased towards extraversion.

Chris Parker: Oh, yes.

Araz Najarian: That always annoyed me. The people who have a tendency to think out loud—to think while they’re talking—don’t give any space for others who need time to first reflect and gather their thoughts. Both ways of thinking are tremendously valuable. Even if you’re an extroverted thinker, take the time to “extrovert” on a piece of paper with yourself first.

We feel a meeting has to be all about talking, but actually, silence in meetings is golden. Instead of talking about something we haven’t read, let’s take five minutes and all sit silent and read it together.

Chris Parker: Or postpone the meeting.

Araz Najarian: Or postpone the meeting. Or, have people absorb the input, have that silence, and write their thoughts down before they extrovert them. People are scared of it. We don’t like silence or breaks.

Chris Parker: I wonder if there’s a cultural dimension. I’m generalizing, but it’s kind of the American/Anglo hierarchical approach, the “ESTJ leader” dictating , as opposed to what I see in the Netherlands, which is much more consensus-driven. Here, to be silent is not appreciated. It’s like, “Wait a second, we all have opinions. What’s yours?” We all have to have our say.

Araz Najarian: Yes, we all have to have our say. Properly facilitated workshops, of course, are designed for this. Let’s make sure the “wallflowers” are engaged and there’s the right time for the right energies.

Araz Najarian: Understanding this in a team makes it easier. If I’m an extroverted thinker with an introverted thinker, I can label it: “Look, I’d like to share this with you out loud. Is this the right moment?” An introverted thinker, when speaking, has already completed their thinking and is stating their conclusion. An extroverted thinker is thinking out loud and hasn’t reached the conclusion yet. That can be very confusing!

Chris Parker: When I’m coaching, my introversion helps because I’m listening a lot, and then able to look for those unexpected queries to jiggle the conversation.

Chris Parker: In that meeting, you mentioned the SPI (Strategizing Preference Indicator). You mentioned strategizing as a verb. Can you introduce us to the SPI? I was curious, so I took it, and we now have my results. What is the SPI, and how do you use it?

Araz Najarian: Yeah. Before we look at your results, what is the SPI? It was developed by Michael [Newman]. It’s diving into dimensions most relevant for problem-solving, because strategizing is essentially problem-solving —or opportunity creation.

It is a Jungian-based tool, so you can see the connection to MBTI. It takes two of those dimensions.

The first dimension is: How do we like to receive and trust information? This is the preference toward Sensing (factual, concrete, realistic, sequential) versus Intuition (big picture, seeing connections, hearing the bigger story).

The second dimension is our attitude to the external world. Do I look for options and see possibilities? Or do I see decisions that I need to take to bring order? This is the Exploring (open) preference versus the Ordering (judging/closing) preference.

This shows up in teams. Someone with an “Order” preference works toward a deadline in a sequential, organized way, maybe finishing early. Somebody with an “Explore” preference might be like a bumblebee, going around, and then in a final burst of stress, they deliver. That can cause tension.

Araz Najarian: The SPI report shows your dominant preference, your starting point. We describe it as a rainbow: you have your dominant, secondary, tertiary, and inferior (the one you’re least comfortable with, or that comes out under stress).

Chris Parker: So if you have six to eight people on a leadership team, how do you use this? The test was super quick, like 20 statements.

Araz Najarian: Usually, we invite everyone on the team to complete the questionnaire, just like you did. Then, in a live session (online or face-to-face), we debrief. I use an exercise: Which hand do you write with? That’s your dominant hand, your preference. If I put the pen in my left hand, I’m not skilled at it because I haven’t trained it. (My mom was forced to be ambidextrous, but she still prefers her left hand).

Then, we invite everyone to read their report and validate it. Most people recognize themselves.

What’s interesting is to then see the team picture—where are we all in relation to each other? Then I love to put them under stress. We give them a problem to solve right now that has nothing to do with their context. This way, nobody is the “expert,” and we don’t fall into our usual traps. When we’re under pressure, we revert to our default preferences.

Chris Parker: So, you run a simulation activity, put them under stress, and then process that. Great.

Araz Najarian: And then we process it. We have a conversation about what went well and why—not about the content (it’s just a puzzle), but about how we were interacting.

Araz Najarian: I was recently using this with a new team I see every quarter. They were spread across the preferences, but several of them were dominant “Improvisers.”

I mirrored something back to them. The day before, they were looking at strategic choices. They got to the end of the day and deprioritized prioritization. They had all their options and then said, “We’re not going to prioritize spending time on prioritizing.”

I told them, “Do you recognize that’s a bias in your team?” The light bulb went on. They realized, “Oh my god, we just walked right into our preference.” They were all comfortable leaving with that ambiguity.

If they had had a few more “Optimizers” or “Visionaries” in the room, those people might have felt more uncomfortable, saying, “Guys, we need to agree on a date and when this needs to be done.” We had to force that moment to agree this was important, because they needed to give clarity to the organization on what they are and are not going to do.

Chris Parker: I’m thinking of a person I worked with, a head of operations. We had very different opinions. I think in my career, because I’m navigating the middle, I’m a professional generalist; I can adapt. But I do tend toward times of change. When people call me, I describe it: “If you’re looking for someone to squeak out a few percentages of efficiency, I’m not that person. If you want to change, transform, break, and rebuild, I am absolutely your person.” I’m aware there are much better people suited for that important job that is just not me.

In my work in IT and digital, it’s so easy to criticize the past. But you have to realize the past was made by people with different preferences, and there was a good reason back then for that decision. People don’t make bad decisions on purpose. The technology is no longer fit for purpose because the time has changed. The people still hanging onto those 15-year-old technologies are the hardcore “Optimizers” keeping it stable. They have blood, sweat, and tears baked into it. And then you have to come in and say, “Well, we’re going to kill your darling.” Expect a reaction.

Araz Najarian: Expect a reaction. And you better have your case very strong, because they’ve been working on it for 15 years and know it better than you ever will.

Chris Parker: There’s self-awareness there, for sure.

Araz Najarian: That “wisdom of the past” is important. We should try to understand why the system is the way it is. I remember with a big food retailer, they had a massive system change, and certain voices—the optimizers—were not listened to. When it went live, it didn’t work. As a retailer, you are stuck. You cannot get goods in and out of your warehouses. It was a massive scandal. There is a huge benefit to that “Optimizer” energy and stability.

Chris Parker: I think in our world, you hear the McKenzie statement that 80% of transformations fail, or 90% of AI projects fail. Something I love to bring into those conversations is: maybe a lot of those should never have started. They’re just bad ideas.

Araz Najarian: Yeah.

Chris Parker: And some of these people, the “voice of reason,” you can call them saboteurs or “resistance to change.” And sometimes they’re right.

Araz Najarian: Yes, sometimes that wisdom is really calling it.

Chris Parker: It’s lazy leadership versus what I call “love leadership.” And sometimes that’s hard, because you have to sit down and embrace people who have a different opinion. “This makes me feel uncomfortable, but I will live in my discomfort so I can understand you, because maybe intuitively I know there’s a nugget of truth in there.” It’s hard work. Lazy leadership is just, “Oh, he’s just a troublemaker.”

Araz Najarian: And then you have the major scandal where your systems don’t work.

Chris Parker: It comes down to leadership. So, in the spirit of wrapping up: If people out there are inspired and going through their strategizing process and want insights into their preferences, how can they do that?

Araz Najarian: I think the easiest is to get in touch for a conversation. We always want to make sure it makes sense to be using this in this moment. Let’s not just get excited because it’s new and shiny. Sometimes it’s not the right setup.

It first starts with a conversation: “Hey, what’s happening? Why did you get excited about it? And could we actually give follow-up to it?” It’s not a one-off; it’s something we have a commitment as a team to return to and reflect on.

Chris Parker: Yeah, and going back to the principles: have a very clear reason.

Chris Parker: Yes.

Chris Parker: And I think, also, have guidance. Don’t self-administer them. Having a coach or a trained external “sherpa” on the way can help.

Araz Najarian: I would say certainly not debriefing these things on your own.

Chris Parker: Not yet. I can imagine AI will get there, but even then, make sure it’s a well-trained AI used for the right reasons. So, you can get a hold of Araz at elpnetwork.com. I’ll include that in the show notes, and also Araz Najarian on LinkedIn.

I was really positively triggered by the engagement with the ELP group on this. And then I said, “Well, let me do this SPI thing, and let’s process this in the podcast.” Some might say that’s vulnerable, but I think it adds richness for the listener to understand what it is and how it relates to someone.

So, let’s look at mine. It’s a 2×2 matrix. Top-left is “Visionary,” top-right is “Explorer,” bottom-left is “Optimizer,” and bottom-right is “Improviser.”

I am in the top-right “Explorer” quadrant, but I’m in the bottom-left of that, so I’m really close to the center. The dotted line (my zone of comfort) is pretty wide, stretching a little to the north.

It says my first preference is Explorer. Second is Visionary. The one I “find it harder to use” is Optimizer, which is the furthest away. What does this mean?

As I said, I tend toward the middle. But “Explorer”? Yes, you could call me an adventurer. I’m drawn to that term. When I read the description—”create global concepts and connections,” “embrace and enable change,” “see hidden possibilities,” “generate options before deciding,” “embrace freedom”—I’m like, “Tick, tick, tick.” And when I’m “going crazy” (the dark side), it says I can become “rebellious.”

When you saw this representation of me, what are a few things that you would shout out?

Araz Najarian: A few things. One, when you showed me and we looked at that picture together, based on my interactions and how we know each other, I recognized that.

What’s interesting about your zone of comfort is that it’s relatively wide; you were using all different parts of the scale when responding. (Some people have a very narrow zone). Your zone stretches further into the “Visionary” and “Explorer” quadrants, which I recognize in the work we’ve done together. You identify new paths forward, explore new innovations, and are always out there saying, “What if I tried this?”

In terms of the “Visionary” aspect, you’re living in the world of possibilities, but the Visionary also brings a framework to it. That’s probably a skill you’ve developed. You need a framework to be able to filter and make decisions, because you can’t make everybody go after all the options.

Your third preference is “Improviser” (making it real, experimenting), and your fourth, outside your comfort zone, is “Optimizer.” I’m thinking you might encounter tension with people who have a dominant Optimizer preference. They start with reality, saying, “Why the hell are we doing something different when it’s been proven successful? There’s stability here we need to leverage.” If you come up with an idea they don’t see connected to reality, they might think, “You don’t know what you’re talking about.”

Chris Parker: I know that’s not my preference. We’re more similar.

Chris Parker: Araz Najarian, thank you so much for this. This has been great.

Araz Najarian: Thanks, Chris.

Sign up for insights on product leadership, AI transformation, and interim executive effectiveness.

Ebullient needs the information you provide to inform you about products and services to help you succeed. You may unsubscribe at any time. Please review our Privacy Policy for more information.